Couples

Mother-in-Law’s Levis

Clothes, fabric, mother-in-law’s jeans, slazenger socks. 114 x 151 cm (2023)

Photos © Hugo Glendinning

Roses

Clothes, fabric, old dress, tights, socks. 118 x 163 cm (2023)

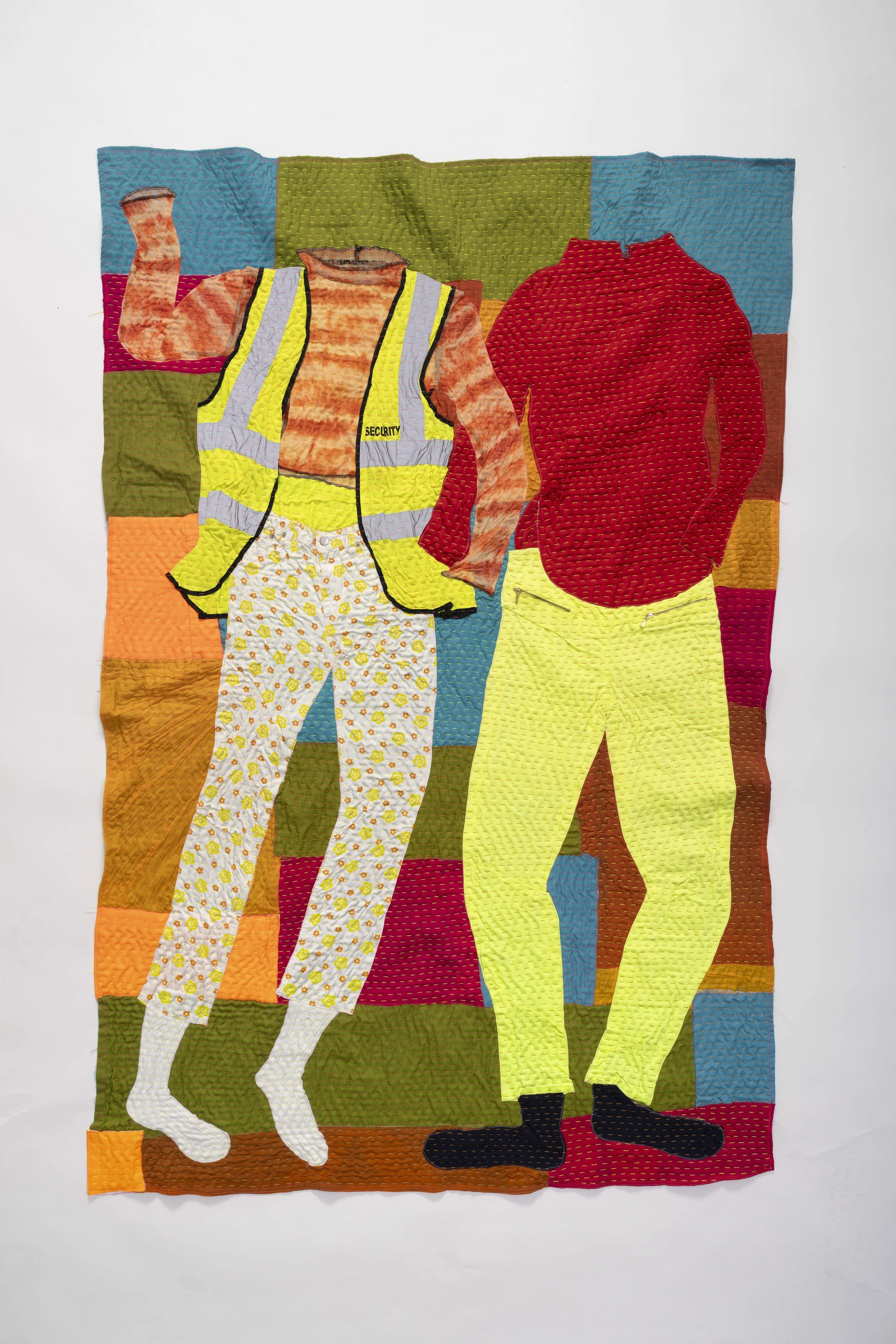

Security

Clothes, fabric, hi-vis vest, socks. 120 x 191 cm (2024)

Dad’s leopard print trousers

Clothes, fabric, fur coat, dad’s trousers, socks. 92 x 165 cm (2023)

Laura Ashley (Skiathos)

Clothes, fabric, tea towel, Laura Ashley dress, tights. 123 x 195 cm (2023)

Charlie

Clothes, fabric 127 x 180 cm (2024) WIP

Couples

Textiles are not made to last. They are meant to be taken down and rolled up, made into something else. Textiles are tied to loss in the moment of their making, a transformation from one thing (string, other fabrics) to another (blanket, curtain, screen, tent, dress). Sewing is too homely, too easily be made in a bed or on a sofa. Stitching feels more equivalent to writing a diary, a private, inane activity, done in the kind of unproductive time that must be stolen for oneself.

Hand-sewn textiles resist capitalist ideas of time as money, in that they are not replicable or scalable. The labour of sewing a hand-made textile can never be recouped in monetary value. In this sense, stitching often feels like actively wasting time, like you should be doing something else more productive. They are also, in many ways, inherently queer, in that they are in a constant state of becoming, of being unmade and reworked, subject to use and degradation.

Saving clothing and keeping scraps is part of working with fabric, whether making clothes or furnishings. Worn clothing of loved ones, unwanted hand me downs, charity shop finds and factory seconds, each intimately tied to their previous wearers and makers but also with waste, mix up. Every piece of clothing is potential trash, out of fashion, out of time, one slip away from landfill. Waste is often used to strengthen worn fabric with applique, to make new clothes or pieced patchwork, transforming mass-produced textiles into unique objects that have deep associations with their maker. Cutting up and stitching together, stitching over, is a kind of life-extension and a form of vandalism.

The running stitch is the simplest of all the embroidery stitches. The needle ‘runs’ along the ground material, making stitches of more or less equal length. Normally there is more thread visible on the surface of the cloth than on the underside. The running stitch, also known as straight stitch, is often used for outlining and as a foundation for other, composite stitches. It is a starting place, quickly made and easily unpicked. When making a running stitch to fix several layers of cloth together, it requires a surprising amount of force to push the needle through several layers of fabric. It is a bodily process, stitching with the weight of it all on your lap.

Time stretches out the way fabric does. Stitching doesn’t so much mark time as defy it – a stitched textile is imbued with the time it took to make it, hours that were lost to the stitcher. Stitched time is non-linear, done backwards or sideways as well as forwards, sometimes faster and sometimes slower. Stitched time is also narrative; stories are spun, woven and embroidered. Stitching might look like killing time, but it is a generative, pleasure-giving kind of labour, restful and resistive.

Alice Hattrick

February 2025